Last Saturday The Sovereign Weekly hosted it’s first ever Space on X.com – something we hope to repeat on a weekly basis.

The discussion, which was very interesting and engaging, brought out some points, one of which I would like to address in this article.

Morals vs Ethics

As long as I have known these to be distinct from one another, I have thought of morality as being the principles one believes in, whereas ethics were how one applies their morals in everyday life, in light of situation and circumstance.

In other words, while one’s morality might be that it is evil to kill another human being, ethically it might be right to kill another human being if, for example, it is necessary to defend one’s own life from being taken by that same human being.

So, when trying to define ‘the Good’, as we have been trying to do since the onset of this thought experiment, and having made the proposition that human life itself could be ‘the Good’, are we thinking about human life as a moral good, or as an ethically right thing?

By the way, if you, the reader, sense a hint of difficulty with my attempt to convert thoughts pertaining to this subject into text, your senses are not lying to you.

The Goodness of Functionality

Early on we tasked ourselves with Defining the Good, and thought that that which is good is also functional. At least according to the Germanic origins of the English word ‘good’ it seems that there is an intrinsic relationship between good and functionality, principle and practice, morality and ethic. To the point where one could say that that which is functional is good, and that which is ethical is moral.

This raises an interesting question – which comes first: moral or ethic?

While I do think that it is possible for morals to come before ethics, I think that this practice would be rather inferior, and therefore short-lived, compared to the practice of ethics forming one’s morals.

Let me try to explain myself.

If one views ethics as being downstream from morals, one would then have to demonstrate the origin of morals. Most people would ultimately point to some piece of text as the source for their morals, which, more or less, is to say that they acquire their morality from what other humans have said are the correct morals. In this case, it seems that morality would, at some point in human history, have stemmed from an arbitrary selection of what is “good” and what is “evil”. Arbitrariness is a rather reckless characteristic to apply to something as powerful as morality, and I would not expect that morality to stand the test of time.

On the other hand, if one views ethics as the building blocks of morality, we would have to ask where ethics are derived from. This is where the idea of the goodness of functionality might be of interest.

Is it not true that an ethic is something which is practical in real-world circumstances? And does not the word practical, like functional, denote there being an end which is served by whatever we deem to be practical or functional?

In the realm of possible human behaviors, the behavior of killing other humans does not lend itself easily to being functional or practical towards ensuring, or furthering, human life.

Yes, in certain, very specific situations, it might be necessary to kill another human in order to secure human life, however this would not be a first-order action, but rather a reaction.

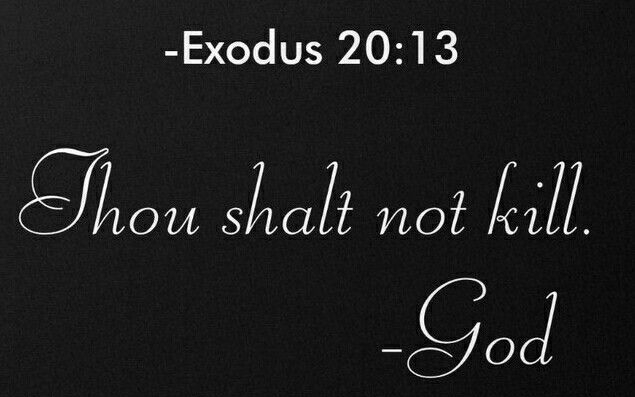

Hence, what is not practical, nor functional, would not be ethical, and therefore we would have a building block for our morality which says ‘Thou shalt not kill’.

But I am sure we all spotted the leap that was taken in this line of logic. Our moral, ‘Thou shalt not kill‘, was based on an ethic, which was based on what is, or is not, practical, which was based on the notion of ensuring human life.

This is the point at which things become so incredibly fundamental that there is probably nothing beneath it. Human life itself must be the fundamental axiom upon which morals and ethics, good and evil, right and wrong, are created. It seems to me that at the most fundamental of fundamental layers, we have to be able to agree that human life should exist.

Power of Simplicity

But perhaps I am stating the obvious and should rather be asking where exactly that takes us.

After all, even if we were to agree that human life should exist, how is that of any use going forward?

I suspect that this simple truth may be quite a bit more powerful than we give it credit for.

But in order to see just how useful it is, we have to push it to it’s breaking point.

That is precisely what is being attempted here, and I think, so far, we have been able to derive a handful or two of things which are functional, and therefore ethical, and therefore form the basis for (a) morality.

Ideals vs Reality

Morals and ethics can also be seen in terms of ideals vs reality, where morals are our ideals, and ethics are our morals getting a reality-check.

Similar to principle and practice, ideals and reality also relate to one another.

If a society has the goal, or ideal, of becoming professional swimmers, and the individuals, who make up this society, act on that ideal in the real world, even though most will not become professional swimmers, as a society they will most likely improve in their swimming skills. Acting on one’s ideals, shapes one’s reality.

However, the acting out of the ideal has to be subject to the situation and circumstance of reality.

Is there water nearby? Is the water clean and safe? How well can the individual swim? Etc …

If one were to ignore reality and attempt to implement the ideal without any adaptation to reality, they would most likely fatally fail.

Ideals are subject to reality. Ideals are also derived from reality, as morals are derived from ethics.

This is because ideals are essentially the result of humans taking what we understand to be functional in reality, such as the ability of humans to swim, and elevating it to a higher order attainment.

Morality, as an ideal, is also a precarious thing to attempt to implement without taking into account the situation and circumstance of reality. Which is why I think it is vital that ethics, practice, and functionality, are elevated above morals, principles and good, instead of the other way around.

Many will be familiar with the term ‘spirit of the Law’, which is the judicial application of placing ethics above morals, practice above principle … the spirit above the letter.

The Moral Story

I propose that morals stem from ethics, and ethics from what we deem functional.

We begin by trying and failing. But we need a way to essentially codify what works, so that it becomes something easier to pass around, and, most importantly, to the next generations. Thus we take what we deem functional and create an ethic.

Killing humans, as a first-order behavior, is not functional behavior.

The Ethic: “We agree, that we will not run around killing other humans. Only if they pose a threat to our lives, and we have tried to reason with them already, and they cannot be disarmed, and we have … etc”

Enter a life hack – Stories.

Stories were more powerful than any other form of human communication. We told stories of our ancestors, who watched us, and, perhaps, over us, from beyond. We could not see them, but they could always see us.

Over thousands of years our stories took on a life all of their own, and our ancestors became gods. But no matter how elaborate and sophisticated our legends and stories became, one thing remained constant – their most powerful functionality – possibly their core purpose.

Stories gave us the opportunity to take an ethic, which was derived from mere human trial and error, and elevate that ethic to something otherworldly, something supernatural, something godly.

Those who behaved unethically were now acting against our ancestors, against the gods – beings who held sway over the elements of fire, earth, air and water.

The would-be murderer now had to not only contend with an angry mob of villagers, but also, and more frighteningly, with the anger of the gods.

If ethics are the codification of functionality, then morality is the codification of ethics.

In Conclusion

In having written all of the above, I, by no means, think I have done the subject justice, but hopefully something there gives reason to ponder.

I’ll tie a bow in this article with the following quotation:

“Create all the happiness you are able to create; remove all the misery you are able to remove. Every day will allow you, –will invite you to add something to the pleasure of others, –or to diminish something of their pains.”

― Jeremy Bentham